Elixir: HTTP requests and HTTPoison

When accessing a website, a request is made to a server and we receive a response in the form of a web-page. This request/response is called HTTP, or Hypertext Transfer Protocol. An HTTP request is made by a client and an HTTP response is made by the server it is accessing.

The request message comes in the form of the url that we type into the browser. A url can be broken down into parts which explain how that message is put together:

The “host” here points to the server that we are accessing, this is where the information we are requesting is stored. Next the “resource path” leads us to the files that we need, and a “query” will provide strings for processing by the web-page logic.

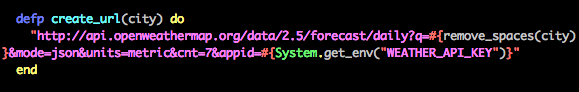

In the case of the url written to request information from Open Weather Data API in a previous post about environment variables, we can see the different parts of the request message below:

http = protocol

api/openweathermap.org/ = host

data/2.5/forecast/daily = resource path

q=#{remove_spaces(city)}&mode=json&units=metric&cnt=7&appid=#{System.get_env("WEATHER_API_KEY}" = query

This particular query requires a city to be passed to it, a mode of either json or xml (the type of data the request returns), a units option of either metric or imperial/US and the registrants appid, or api key, in our case hidden as an environment variable.

Types of Requests

HTTP requests most commonly use four different verbs in order to determine the type of request. These verbs are:

- GET - retrieves information that already exists.

- POST - creates new information to be stored.

- PUT - updates information that already exists.

- DELETE - deletes information that already exists.

An HTTP response

An HTTP request always receives a response, even if the request is unsuccessful. If the request is successful, the response is a status code and the information/files requested; if the request fails, the response is a status code usually with some kind of error message.

Status codes tell us details on the status of the request. They present themselves as a three digit number. Some different status codes are:

- 100 - 199 : Informational Messages, this range of status codes is provisional. For instance 100 is the status code for “Continue”.

- 200 - 299 : Successful, this range of messages tells the client that the message was successfully processed.

- 300 - 399 : Redirection, this sends a response to the client to jump to a different URL in order to access the resource.

- 400 - 499 : Client Error, this range of status codes tells the client that they are at fault, perhaps for requesting an invalid resource or making a bad request, sometimes due to a mistyped url

- 500 - 599 : Server Error, this range of status codes tells the client that the error is on the server side.

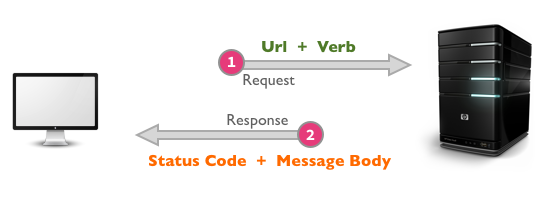

The image below shows what the HTTP request/response needs and delivers. We must give the url along with a get, post, put or delete request, and, if successful, we will receive a status code of 200 ok and a body providing us with the information we sought.

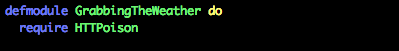

Using the HTTPoison Library in Elixir

HTTPoison provides us with an HTTP client for our Elixir application. It provides us with everything we need for interacting with external services.

The documentation, which includes functions for the different types of http request verbs can be found on hexdocs.

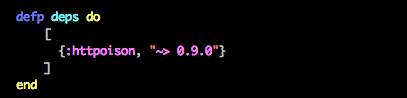

In order to use HTTPoison, simply open your mix.exs file and add it as a dependency here:

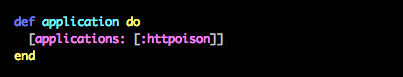

And in the application function here:

Now run the command mix deps.get, and watch HTTPoison configure in your project.

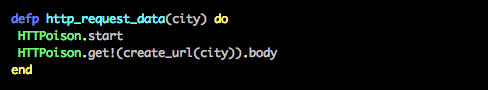

HTTPoison must be required in the module that is using it, like so:

Because HTTPoison runs like a process in the background of your application, it must be called to start. Here we are using it to send a GET request in order to retreive information from the Open Weather Data API. The get request is called upon the url in the create_url function that can be seen as an image at the top of this page. As previously explained, the HTTP response will consist of a status code and a message body. We are interested in parsing information from the message body and so we use the suffix function .body.

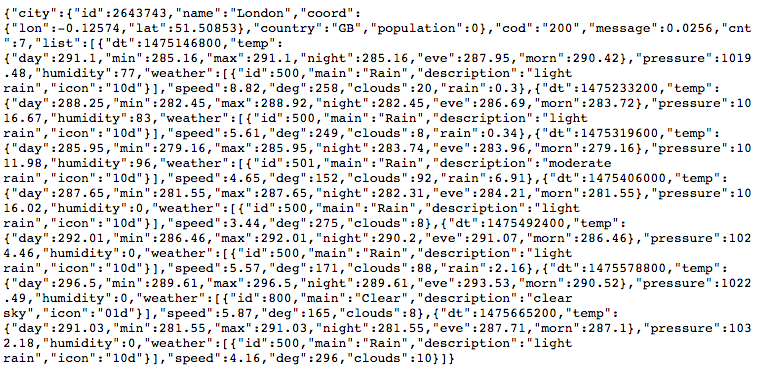

This will pass us a JSON file of data, which will look something like this:

Woah!

How we decipher this and convert it into something which Elixir understands will be convered in the next post…